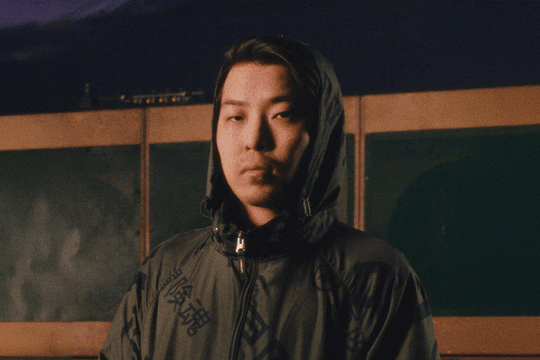

Matthew Herbert interview: "It's about wanting to bear witness."

In conversation, Matthew Herbert is considered. He decides what to say and how to say it with a great deal of care, and would be amiss to lose a train of thought: always coming back to the central point no matter how divergent or anecdotal the response becomes. It's a learned trait that seems to have served him well. Having spent nearly twenty years recording sounds that explore the place of the living being within an active, often cruel world, he's become known for answering questions of his work with as many – if not more – questions in return.

After a backlash from animal rights activists about his last album 'One Pig', which saw Herbert observe the slaughter of a farmed pig and then use its carcass to create sound, the critical attention surrounding his new album 'The End Of Silence' has once again prompted the producer to discuss (or defend) his radical approach. Taking a five second sound clip of a bomb dropping in Libya and re-structuring it into a forty-five minute recording, 'The End Of Silence' raises issues of the representation of warfare in a digital age, the role of the eyewitness as spectator, the paradox between the necessity and impossibility of testimony, and the artistic imperative to explore such issues from a remote, often privileged vantage point.

Nearly two decades into a career of releasing conceptual music of this kind, Herbert remains an intriguing figure. His approach is in part deliberately evasive. In not wanting to ascribe any one discipline or theory to his working methods some view his motivations for each project as at best inspired and at worst opportunistic, yet his career is one that listeners are drawn to time and again for a variety of reasons. Some arrive at his work with a curiosity born of controversy, others return out of loyalty to his self-styled auteur persona, but more often than not with the basic understanding that Herbert's emotional investment in each release is as much a part of the narrative built around his work as the work itself.

In discussing 'The End Of Silence', Herbert opened up to Dummy about what motivated him to work on this project, how it affected his understanding of recorded sound as a medium, and answered criticism of the album in his typically forthright and emotive way.

There has been a heavy hand of criticism swung at The End Of Silence. In particular, that for an album made from a recording of a falling bomb in Libya, it feels very distant and non-human. What would you say to this?

Matthew Herbert: The whole point of The End Of Silence is that it is about distance. It is about mediation. On 'One Pig', every single sound on that I take complete responsibility for. I spent over a year of my life, in rain, snow, sun and wind, recording every single sound on that record and turning it into music. This is about something else entirely. This is about a second hand experience, so the questions it raises aren't the same as that of One Pig. How do you feel about a medium that projects this recording, as well as the event and the recording of the event itself? How do we even know it's a bomb going off? We just have someone's word for it. I happen to believe that he's telling the truth but, is there any truth in a recording? For me, there's all sorts of complicated positions involved in a process of this kind. I find a real sense of irony in the criticism that says that I shouldn't have make the record in the first place, especially in light of criticism I got from PETA about One Pig.

"How do we even know it's a bomb going off? We just have someone's word for it. I happen to believe that he's telling the truth but, is there any truth in a recording?" Matthew Herbert

Well, just by saying “it's a record about distance” doesn't negate the fact that you, as an individual, have taken it upon yourself to make such a record. Your motivation strikes me as the inverse of that of Fatima Al-Qadiri's 'Desert Strike' EP.You're not an eyewitness and your testimony isn't based on first hand knowledge, so what was your imperative in making 'The End of Silence'?

Matthew Herbert: Well, my imperative was to try and make sense of an experience that I wasn't privy to. I suspect that anybody who heard this sound for real isn't particularly interested in going back and re-living it. I know that Sebastian, the photographer who recorded the sound, can't listen to the record all the way through. I think that it's a very complicated position and a complicated set of circumstances, and I feel that I've tried to construct a process with as much integrity and openness as possible. I try to set it up in a way whereby I feel that how the project is put together – how the artwork is done, how it's framed, what the titles are, the structure of the piece, who I recorded it with, where I recorded it, what the recording process was – both asks and answers questions. I want to think about and around the subject in a meditative way. I don't think you can go into making a record like this already having a finite, clean and simple position on the material or the process involved.

What was the recording process like? I'm aware that it was made by yourself and three others in a live jam session?

Matthew Herbert: Yeah. The whole thing was recorded in three days. I wrote the basis of the material and then we as a band improvised with and around that material. We set up microphones outside the recording studio as well as a way of acknowledging the distance between us and the horror that went on; between my privileges as an artist and this terror removed from my own experience, between life and death, between now and history. So for me, where, when and why those microphones are used are all part of us trying to be presently aware of and lay bare the process as well.

"I'm not willing to just accept that all these things are inevitable, but I can't explore everything. I can't go to the Amazon and record a tree being chopped down as well as record bombs dropping in Libya. You have to choose your moments. You have to choose the direction of your microphone." Matthew Herbert

So in creating a self-aware, active space in which you acknowledge the distance and time between yourselves making the record and the original event itself, you feel that you've answered the criticism of the final record sounding “distant”?

Matthew Herbert: I wouldn't put it exactly like that, but it's not far off. For me, it's about wanting to bear witness and wanting to remember this moment in order to make sense of it. Not just let another bomb explode and another person die, another distant terror. I'm not willing to just accept that all these things are inevitable, but I can't explore everything. I can't go to the Amazon and record a tree being chopped down as well as record bombs dropping in Libya. You have to choose your moments. You have to choose the direction of your microphone. I live a life of the most extraordinary privilege, I really do. I travel the world playing my music. My life is not under threat and I'm free to make criticisms, but with such privilege comes responsibility. Part of that is in telling the stories of those whose lack of privilege is based on the historical context which has allowed mine in the first place.

In making a record like this, I would naturally assume that a large part of your imperative is to provoke a reaction from the listener. One that would make them think about the subject matter, the way it's projected, and so on. It's such a visceral sound, so retaining that is something that I would see as necessary in order for it to not become “distant”. What do you think the effect of the record on a listener will be in this respect?

Matthew Herbert: I'm very strongly opposed to the concept of an “ideal listener” or “ideal reaction”. As I get older I feel that it's an increasingly alien idea to me. I'm in conversation with Sebastian at the moment about the process of making the record, and what it's confirmed for me is that I'm very, very wary of (and sort of loathe to) talking about “audiences” and “listeners” for this kind of thing. I don't really believe in the idea of fans and audiences. I just think you have listeners at different points in your life. Having said that though, I would go as far as to say that a record like this is not really meant for those that went through it in the first place.

How do you feel elements of trauma are expressed in the record?

Matthew Herbert: There's a level crossing near my home, and there must be a warning sign not far off the bend that leads to the tracks because four times an hour for ten years, I heard this “duh-dah” sound. Four of those ten years was when I had my recording studio in my home. I don't have any soundproofing because I like the sounds of the outside world to filter into my work, so this “duh-dah” is all over my recordings.

"The 'meaning' of sound is constantly in flux. Somebody listening to 'The End Of Silence' may suddenly find themselves in a position next year where they'll hear one of these sounds for real. Then what? I mean, they could absolutely not give a shit about this record at all, and they're allowed to, but what if you were to hear a bomb drop in real life? It's no longer just a sound. It's a matter of life or death." Matthew Herbert

Like a personal time signature almost?

Matthew Herbert: Yeah, kind of. For a long time it was like, “Aww, that's kind of cute, that's kind of funny”, but then somebody that I knew and liked – not a close friend, but someone I cared about – she killed herself on the railway line. Then two weeks later, somebody else did. Then a month later, somebody else did. I only live in a small town so this was really awful. In a six or seven week period over Christmas three people killed themselves. Every time I hear that “duh-dah” noise now, I think about them. I can't shake it. It's gone back and retrospectively changed all the meaning of all that music for me. Not in its entirety, but in a way I never could have expected.

So, what does that sound mean? What's the ideal response to that sound? What does it mean to the train driver who saw them jump? Or the husband of the woman who jumped? Which position on the sound is the right one to take – the day before my friend died? The day after? A year later? There isn't an ideal response. The 'meaning' of sound is constantly in flux. Somebody listening to 'The End Of Silence' may suddenly find themselves in a position next year where they'll hear one of these sounds for real. Then what? I mean, they could absolutely not give a shit about this record at all, and they're allowed to, but what if you were to hear a bomb drop in real life? It's no longer just a sound. It's a matter of life or death. It would completely change everything.

What do you think this means for recorded sound as a medium, and what do you think you would say to someone who was about to listen to 'The End Of Silence' for the first time?

Matthew Herbert: I'd say, “Listen to this. I personally found this an extraordinary noise. One that I've never heard before. One that's a million miles away from anything you'll maybe heard before.” I ask questions about this record all the time. “How do you feel about it? Do you feel the same way now as when you first heard it? How about hearing it really quietly, really loudly, three times, one hundred times? Should I play this sound to my six year old son and if I do, is his reaction any more of less valid or interesting than anybody else's?” There's just thousands of questions.

In terms of a reaction it's always the same for me: I'd like people to listen to the world more carefully. I find recorded sound like this so exciting. I think it's a huge liberation. If I wrote a song with a guitar and sang some lyrics about a bomb exploding in Libya, you'd know exactly what I thought. The room for interpretation would – bar some semantic ambiguity in the lyrics – be really limited. With instrumental music, we have to learn how to listen differently. Sound is in flux in a way that other recorded medium is less so. That doesn't make my record brilliant, that's another issue entirely, but there's been a fundamental shift. It's not impressionism anymore, it's a documentary. It's like moving from the painting to the camera.

"If I wrote a song with a guitar and sang some lyrics about a bomb exploding in Libya, you'd know exactly what I thought. The room for interpretation would be really limited. With instrumental music, we have to learn how to listen differently." Matthew Herbert

That reminds me of something Susan Sontag once wrote: “Photographs are not much help if the task is to understand. Narratives can make us understand. Photographs do something else – they haunt us.” It makes me think there's a very fine line between sound, music and narrative on 'The End Of Silence'. Where do you place the album in this regard? Do you consider 'The End Of Silence' an album of music?

Matthew Herbert: I absolutely consider it music, I do, but I just don't think the word “music” quite sort of works anymore. Not just with 'The End Of Silence' though. The piece of music on my phone telling me someone is calling me serves a completely different purpose to Wagner's Ring Cycle. We have fine art, design, pop art, modern art – we have all these distinctions in art that we don't really have in music yet.

What do you mean by “We don't have any distinctions within music”?

Matthew Herbert: Well there's no fine art equivalent of music. “Fine music” doesn't exist.

Do you mean in terms of generic definition, and cultural hierarchies of how we define and value music? Surely that serves a similar purpose?

Matthew Herbert: I'm talking about the language of music rather than the music itself. I'm saying that there isn't the proper categories. There's no “haute couture music”. There isn't a description within the taxonomy of music. People talk about film as painting with light, so in that sense film is at it's best a continuation of that painterly tradition through a different medium. In this sense I definitely think of what I do as music, I just think the word “music” is pretty clumsy. You'd have to be a very particular person to listen to this album a lot. I wouldn't listen to this in the house the same way I'd listen to a Marvin Gaye record.

"I definitely think of what I do as music, I just think the word “music” is pretty clumsy." Matthew Herbert

What's really struck me is not what is in the record, but what isn't.

Matthew Herbert: Yeah, it is sparse. It's very sparse. It's a meditation on a landscape in the way that 'One Pig' was a meditation on a portrait. That's not to belittle the lives of the people that were possibly lost as a result of the events that were recorded. I don't want to trivialise that or turn that terror into some kind of bourgeois whimsy, but the final work is a landscape. There's a lot of quietness in there. As I get older, quietness gets more and more important to me.

What I've found interesting in a few of the reviews I've read is that people have commented on the fact that the scary stuff is not the bomb going off, but the gaps in between. You never know when its coming back. That feels realistically horrific to me. When you hear soldiers talk about war they often describe it as “99% boredom, 1% terror”. It's not something that you're in control of, and that's what I was especially aware of in the recording process. When the four of us were recording together there were points where we didn't know who was playing which noise, and it still happens when we play it out live too. It's a very odd process.

The fact that it's a disorientating experience to play live as well is pretty apt considering the subject matter.

Matthew Herbert: Yeah, yeah it is. It's very odd and it's a very hard record to play live. It's very hard to keep listening to as well.

Do you find it difficult to listen to?

Matthew Herbert: I do, but I also know it very well now considering that I've only heard it a few times.

You've only listened to it a few times? Really?

Matthew Herbert: Yeah, but I feel like I could sing the whole thing to you pretty much.

That's a strange use of the word “sing”.

Matthew Herbert: Well, what I mean by that is that I understand the logic of it. I'm really proud of this record. It's an electronic music record played live entirely by musicians without computers. There's no click track, no programming, no editing: it's just three or four takes put together. Stylistically, it feel right. It's taken me twenty years to get to the point where I feel that I can lift the music out of the computer and just play it in an expressive way. The whole album is about listening. The process of writing and performing it is about listening. We need to listen to each other in order to hear what we're doing. We have to listen to the sound again and again to try best understand it. Clearly some people just don't want to know what's there. Some people think we shouldn't have made it. You can hate the music all you like, but I've yet to hear a very convincing argument as to why this sort of record shouldn't be made.

"I think that people have come to this record with all kinds of prejudices and lazy assumptions. It frustrates me because they just haven't really listened properly." Matthew Herbert

One of the arguments that I've heard is that you've taken a very real, human event and removed the human from it through the recording process. What would you say to that?

Matthew Herbert: I think that's absolute, complete bullshit. Total bollocks. Every single note that you hear in 'The End Of Silence' that you could ascribe a pitch to comes from two noises made by humans in the original sound sample. It comes from somebody shouting, and it comes from somebody whistling. Two voices, shouting and whistling in warning. Those are the basis of the bass line, any base noise, keyboards, any melodies that you might hear, are all from that. The percussion on the other hand tends to come from the mechanical sounds. I think that people have come to this record with all kinds of prejudices and lazy assumptions. It frustrates me because they just haven't really listened properly.

That's interesting that you say “properly”, as if there's a correct way to listen.

Matthew Herbert: Well, when I say properly, I mean people don't have enough awareness of how to listen. If you want to find the human element in this piece you can't sit and pick it out as a singular moment. It's all through it. You can trace the genealogy of that one whistle through the whole forty-five minutes. You can hear that whistle mutate, distort, reverb, go through all sorts of changes. It's not so much the spine of the record. It's more, the skin.

What I feel it tries to work towards is a new way of communicating the disaster as event through a different medium. We in the West are constantly bombarded with the visual imagery of warfare: people crying, bodies in the street, clouds of bomb debris, it's just a deluge of suffering that, from our privileged perspective, is gradually losing its 'humanness'. How do you feel recorded sound can challenge our perceptions and contribute to the conversation to how we document such events?

Matthew Herbert: Well, in Syria, the government were setting off sound bombs three times a day in Damascus.

Sorry, what's a sound bomb?

Matthew Herbert: It's just the sound of an explosion played loudly in the open. It's meant to just generally terrify everyone who can hear it into thinking it's potentially a real bomb. It's a physical device but there's no debris. Just the sound of an explosion.

"Sound is a new frontier in storytelling. It's a new medium, a new format, a new sense. We don't have a relationship with recorded sound like we do with recorded image." Matthew Herbert

Really? That's horrible.

Matthew Herbert: It is, but it also demonstrates the power of sound. I feel that sound is a new frontier in storytelling. It's a new medium, a new format, a new sense. I mean, we've only had it for one hundred years. If you go on the internet and search for sounds from the war in Syria, there's nowhere to go. You can go on YouTube and listen to someone on the back of a video clip or something, but there's no place to just listen. We don't have a relationship with recorded sound like we do with recorded image. The people that record and edit sound to make it available to us generally have a great deal of experience and there's all sorts of rules that go with it, all sorts of assumptions and technology built around it, but there's no consensus about the best ways to listen and understand it yet.

Sound is a gateway into the experience because it bypasses issues of language, issues of censorship (for now at least), gender, race, sexuality – it's a much more generous medium in that respect. I think one of the most striking things about the original sound recording that we used is that it doesn't sound like Hollywood. We've heard probably one hundred million explosions in action movies and I can't recall ever hearing something like this. Just, the quality of it. There's something very particular about the whistle and the shout. They're both very loud considering that a bomb is about to explode. They're like yardsticks to measure the explosion against. When it comes to the criticism of the record about the absence of humanity in the record, the sound that the human makes is as loud, if not louder, or at least as clear as, the sound of the bomb falling and exploding. They're two very distinct qualities of sound, but the extraordinary thing about it for me is that it's not fake.

"I think that the most important thing about this record is that the original recording is listened to over and over again. That it's not forgotten. That history doesn't just, slip away unacknowledged." Matthew Herbert

What struck me about the clip is not just that it sounds extremely unclean, but that in its brevity there is so much in it. When I listen to it over and over, I still pick out and pick up on some elements over others that I didn't concentrate on at first. Some bits get louder, others get quieter. They almost take turns in being the focus.

Matthew Herbert: Yeah, I've now listened to the original recording hundreds and hundreds of times and it still does something that you just cant fake. That's scary.

What do you want the lasting effect of this record to be?

Matthew Herbert: I think that the most important thing about this record is that the original recording is listened to over and over again. That it's not forgotten. That history doesn't just, slip away unacknowledged. We have a responsibility to document, discuss and try to understand the world to the best of our abilities.

Have you tried to work in a sense of memorialising within that?

Matthew Herbert: Yes but not just to memorialise: to bring things back into life through the process of documentation. Taking an act of unadulterated and sickening violence and turning it into music. Reflecting on what we've documented. I think there's something of value in that. It's not even about me and the music. It's about this event, this time and these people. That's the most important thing.

Accidental Records released Matthew Herbert's album 'The End of Silence' on 24th June 2013.