"We're about to embark on a course of self-destruction": The Chemical Brothers on what is - and isn't - their Brexit album

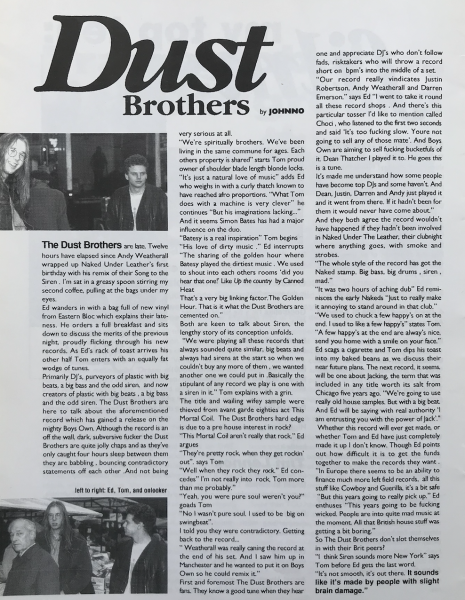

In 1993 I submitted the first-ever interview with Tom Rowlands and Ed Simons to Jockey Slut magazine when they were still known as The Dust Brothers (a name literally borrowed from the renowned Beastie Boys and Beck producers) which underlined the fact that they perhaps didn’t see themselves moving from the underground at the time.

In 1995, with their name changed to the Chemical Brothers (The London Dust Explosion was another potential name – it even got to the logo stage) they had proved to have a knack for making what Tom called “accidental pop records.” ‘Block Rockin’ Beats’, with its mad ululating siren, was a bizarre record to get to Number One in an era when you still had to sell hundreds of thousands to reach pole position.

They made the cover of Jockey Slut five times subsequently with the decade closing with us posing the question: ‘Are these the most important men of the ‘90s?’ (Conclusion: yes, as they appeared Zelig-like through the era influencing everyone from The Prodigy to Oasis to what could be played at club nights).

The last time I quizzed them was in 2003 when they had released a greatest hits collection (‘Singles 93-03’). Usually the coda to a career, they have since released another five Number One albums and collaborated with a Pyramid stage line-up of acts, from The Flaming Lips, Bloc Party, Q-Tip, to Beck. Their latest, ‘No Geography’, eschews the mega names for rising Norwegian singer Aurora – who appears on three tracks – and a sound that nods frequently to the rave period they absorbed and participated in when they met three decades ago at Manchester University. Ahead of the release of their ninth studio album, I sat down with Ed to reflect on the long legacy and discography of the Chemical Brothers.

Right, let’s start off with the album which I’ve had on repeat for the last couple of days. I think it would go straight into your top five best?!

Ed Simons: Yeah, I was pleased with it. I think for me it harks back to the original burst of albums. There was a long line – apart from ‘Further’ – of these quite collaboration-heavy albums. Although there is a big collaboration at the heart of this record with Aurora, there’s a lot more vocal samples and it feels more like the two of us telling some kind of story and expressing ourselves. I think the guest vocalists have been a great part of our music but perhaps it kind of diluted the sense of the two of us.

This is one of the reasons it’s the most coherent sounding album you’ve done from start to finish…

Getting people to sit down and immerse themselves in a whole album is a thing that’s drifting away. And so for us to make an album I felt like it had to have that sense of taking you from one place to another, lots of different emotional tones but with an overarching aesthetic. I think we had the two core ideas really; that because we worked so well with Aurora and she provided enough sort of ideas that we could pursue three tracks with her and then these kind of found sound vocals: they are all different but they all feel like they’re expressing something quite visceral and deep.

It’s a bit shorter as well, I know that might be a bit prosaic but there’s something about how much time people have got to just sit with the same producers, the same writers. There’s enough there but there isn’t too much.

Another thing that links a lot of the tracks are the sound and style of the riffs that hark back to the time you and Tom were going to The Haçienda in 1989, furthered by a couple of Todd Terry samples (on ‘Eve Of Destruction’ and ‘Bango’) from that era. Was that intentional? Looking back to the time when you first met in Manchester 30 years ago?

30 years, too long. It’s nice though isn’t it, I’ve put a photo up of the two of us at Glastonbury today [Ed posted on Facebook a photo of them from the mid-‘90s putting their tents up] and I was like, ‘We have done quite a lot of stuff together you know?’ It’s not really deliberate with the Todd Terry samples, I think we both found ourselves singing [a refrain from Todd Terry’s ‘Weekend’, originally taken from a Class Action song] all the time in the studio as the track didn’t have that on it.

And then actually when we were playing Printworks [in December 2017], we had an early version of ‘Eve Of Destruction’ and wanted to pep it up for the DJ set so we put in the sample from ‘Weekend’ and once it was there it was kind of hard to take it away because it was so good.

It’s always there, it’s in our DNA, it’s a time we both really loved – The Haçienda and the Orbital raves

But it’s not a particularly nostalgic album. I don’t think those kind of riffs or the Todd Terry homage were like a really conscious intention, we certainly haven’t made our 1989 album, but at the same time, it’s always there, it’s in our DNA, it’s a time we both really loved – The Haçienda and the Orbital raves. Maybe it’s seeped through, harking back to something that was really positive in our lives. But yeah, hopefully it’s forward and backwards at the same time.

You decided to use equipment from your mid-‘90s period that you hadn’t used since the first three albums so I guess there was an intention to sort of harness something from the past?

I mean we’ve always used older equipment, we use technology to integrate different impulses. I think particularly with the old samplers we used they have a particular sound, there’s a sort of crunch to the sound of the E-MU sampler and when we started hearing that again it does have an echo, like a little signifier and it takes you back to how those original records were made. But we didn’t make ourselves a particular set of rules.

Tom said in the late ‘90s: ‘Someone said we sound like we could do with another day in the studio and that’s the point, I like things that sound a bit wrong.’ Do you still take that approach?

That’s a good quote from Tom, he’s a very wise man. You try and reach a juxtaposition between too many days in the studio and one day less. I mean, we want the record to sing, we’re really interested in sonics and making it really bring a room alive when the music’s playing and we spend a lot of time mixing it, but there is something about forgetting that and going down that Arthur Russell route – first thought, best thought. It’s very hard, that’s a really hard art particularly when you have got more time. Junior Boy’s Own gave us ten days in the nice studio to do ‘Exit Planet Dust’ – and it wasn’t even particularly a flash studio…

‘I Won’t Back Down’, ‘Give Me My Thunder’, ‘If You Ever Change Your Mind About Leaving It All Behind’, ‘No Geography’, ‘Eve of Destruction’… is this your Brexit album?

That would be a terrible album, our Brexit album! I was just thinking about the records we used to play at The Sunday Social [in 1994] and we used to play The Specials’ ‘You’re Wondering Now’ and you know there’s that lyric: ‘Britain has fallen and now you’re on your own,’ and it used to really resonate, but that was 25 years ago.

There’s not something new that’s particularly happening with Brexit but there’s a sense of real fragmentation and impending chaos and uncertainty and it’s difficult for that not to come through in the music. I mean Tom and I are clearly pretty strong remainers and we feel that this is not a good idea and the culture war that has developed around Brexit – we’re definitely on one side of that.

You know this sense of closed versus open, and you know our music has always been about getting out there and playing, whether it be in Europe or anywhere in the world, and enjoying that process of collaboration and being open to other peoples ideas so, yeah, it’s definitely impacted us. We’re pretty pissed off about it all, because people have been lied to and we’re about to embark on a course of self-destruction which is not great.

There are some positive tracks on the album though like ‘We’ve Got To Try’, ‘Got To Keep On’ and ‘Catch Me I’m Falling’ which reminds me of old unifying rave records with the gospel-style vocal?

Yeah it’s certainly not all doom and gloom – there is something about escape in dance music, isn’t there? Transcendence has always been such an important part of what we feel is good about music, going back to those Haçienda days, Orbital rave days, that feeling of togetherness was a powerful part of it. That smiling face and a thumping bass ideology.

That’s our more explicit Brexit message: that something can survive all these splits.

When you actually dig deep in to the album, there’s something in it that’s about escape and space. The ‘No Geography’ poem is about a love that can survive geographical separation, so connection that doesn’t depend on proximity. That’s our more explicit Brexit message: that something can survive all these splits.

There was a little split in your audience when you posted that Brexit Planet Dust meme with Trump and Brexit on Facebook. You had a slight spat with someone who told the Chemical Brothers to stay out of politics and you weighed in with: ‘I’ll say what I like mate!’

It’s an odd sensation, being told what you are and aren’t allowed to talk about. Look at Gary Lineker: ‘Stick to your football mate’. Yeah it’s an odd world we live in, eh? The entitlement culture is incredible, like how people think they have the right to tell you how things are all the time.

You DJed half a dozen shows in 2017 to test tracks out, is that still a crucial part of the process?

It’s definitely a spur to activity, you know we were just talking about ‘Eve of Destruction’ and how the sample from ‘Weekend’ came about? We thought, we’ve got a DJ set [at Printworks] in a couple of weeks so we’d better get these tracks worked up to play. We played ‘Free Yourself’, ‘Got To Keep On’, ‘Eve of Destruction’ and ‘MAH’ that night. We also actually played a lot of these tracks live before release because we were so excited about them – particularly ‘MAH’ which we played live last year at various European festivals – it seemed to capture something of the prevailing spirit of the age.

It’s probably the first time you’ve actually toured quite big venues, like Ally Pally and had so many new tracks to play.

Over the last four years we’ve just been non-stop playing live, making music, DJing, working a lot and really enjoying it and getting a new lease of life from it all. I had a year where I didn’t play live and there’s nothing that focuses the mind more. I chose to come back and fully commit to playing live – I really missed it when I didn’t do it, but for various reasons I had to take a year out and so I think there’s been a real burst of creativity recently and we’re just sort of non-stop.

So when it came to the decision – should we do some shows before the album? – that was the big part of it. It made it more exciting for us working out these new tracks to play live, and feeling how they fit in with the older numbers.

Having that time off from Tom – he even played Glastonbury on his own with the visuals director next to him in your usual place – did that strengthen your relationship, do you think? Having a bit of time apart?

Well, we always get on – we haven’t really ever fallen out, but I had something else I was doing and needed to take the time out. We’d just finished ‘Born in the Echoes’ so Tom wanted to tour and he found a way of doing it. I mean Adam Smith [who did the visuals] joined and it was fun and it was fun for me to go and actually watch The Chemical Brothers, which I did in Paris.

It was weird approaching the dressing room afterwards, I was like: ‘What do I do here? Do I come in?’

How did that feel?

A bit weird, but it was an interesting experience. It was weird approaching the dressing room afterwards, I was like: ‘What do I do here? Do I come in?’

I didn’t go to Glastonbury the year that Tom and Adam did it. I thought if I went, they’d be like, ‘Fancy coming on?’ They had me on FaceTime in the dressing room before – I was the calming voice on the mobile just sat on a chair rather that doing the usual pacing around the room thinking about all the things that could go wrong.

In terms of our relationship, because it has been album, tour, album, tour for a long time and I think it can feel quite relentless, but I think having sort of stepped out and then chosen to go back in I feel – oh I love it actually, I love playing live. We have the same road crew that we’ve pretty much had since the beginning and we just have a really good time travelling around.

Are you looking forward to Glastonbury? You’ve obviously got big ties with the festival, you’ve played it many times and Michael Eavis even got married to ‘Hey Boy Hey Girl’, didn’t he?

I believe so, yeah. I’m really looking forward to it, we’re playing the Saturday night – party night – and it’s just a fantastic place to play for us. We used to go down with our tent and camp and there’s just one place where everyone used to hang out and definitely have good memories, and I find it exciting checking out the new things, Block9 – there’s always something to discover there. We’re playing in Cornwall the night before so it’ll be nice to arrive once everyone’s calmed down a little bit.

This interview will go live the week you play The Social bar in Soho [there has been a recent campaign to save the Heavenly Records-owned venue]. Being residents of the epoch-making Sunday Social at the Albany pub in 1994 it did really shift you up a gear and shine a spotlight on you. How important do you feel that club was?

Oh, it was a brilliant night. People really enjoyed themselves. We were doing a lot of remixes for more traditional bands – no, that’s the wrong word… bands like The Charlatans and Primal Scream and Saint Etienne so we had all those new records to play, we were making ‘Exit Planet Dust’, we had our Prodigy remix (‘Voodoo People’), stuff like that. It was all new and we found a way of kind of playing those records, ‘Leave Home’ and the early stuff like ‘Chemical Beats’. It all kind of works together and Heavenly gave it a really good context because they would have people like Andy Weatherall and X-press 2, you know just a really good selection of people. It was a really good night of music.

It was also very odd because the first night we did it there was like 70 people there, we just kind of invented a set to play, made it up as we went along, and then the next week there was a roadblock straight away, there were queues and it was really popular and chaotic. Lots of the big stars of the day used to come down.

Sunday night is so sacred to me now. I have to be in my own house by five on a Sunday, I’m not going anywhere…

I came down from Manchester to that second one… on a Sunday evening!

Yeah it was suddenly like, ‘Wow, this is a happy thing’. It was great, it was a really amazing time, we only did 14 of them at The Albany. We met Tim Burgess and Beth Orton they came down and did vocals on the album and a lot of those connections were forged. I think Noel Gallagher used to come quite a lot and stand behind us. Yeah, it was a great time.

Sunday night is so sacred to me now. I have to be in my own house by five on a Sunday, I’m not going anywhere, that’s it, I’m done. And the idea of trooping off to a nightclub… well it was 20 years ago.

25.

25, sorry, yeah. So we’re really looking forward to doing it. Some of these records they’ve taken a bit of digging out, but they sound great. I was playing our remix of Bomb the Bass [‘Bug Powder Dust’] and, wow, it used to cause mayhem in those times and then that scene became a little bit dismissed, people dismissed it as ‘big beat’, but listening to some of those records they were really great, you know?

I was looking back at some old issues of Jockey Slut and by the time you’d recorded ‘Surrender’ in 1997 you still felt ‘Chemical Beats’ was the best thing you’d recorded. What do you think your favourite track is now?

That’s a good question, I still say ‘Chemical Beats’ and ‘Song To The Siren’. ‘Chemical Beats’ just sounds amazing, it has that kind of rough edge to it, but it’s so funky. When we play live, I’d say ‘Star Guitar’ I suppose. I would say those are the trinity.

But you know, I like all the new stuff but I think ‘Star Guitar’ sometimes when we play it live, it just has that transcendence, that thing of just really escaping into a depth of feeling and release.

It’s also quite an achievement that you’ve put nine albums out and you haven’t really released a proper stinker at all. But if you had to put one at number nine, which one would it be?

Well only because you’re asking me and I’m not volunteering this information, but I would say maybe ‘Come With Us’? But then ‘Come With Us’ has ‘Star Guitar’ on it…

I know yeah, and ‘Hoops’.

And ‘Hoops’, it does have some really good tracks. It was a strange time and I wish ‘It Began in Africa’ had just been released as a kind of standalone track, I think it sort of dominates the album. So if I really had to say a nine it would be ‘Come With Us’. But I think it was because we had to follow those three albums. They always say the difficult second album – it’s a difficult fourth album…

Around the time of ‘Come With Us’, I asked you the question: ‘Will you still be making Chemical Brothers records when you’re 40?’ and Tom said, ‘Probably not, but we’ll still be making music in some professional capacity.’ What do you think of that now you’re aged 48?

I used to have this thing when I was about 23, I said, ‘Oh I won’t be doing this when I’m 30’. But you just have no idea how you’re gonna feel as the years roll on. I mean I guess the answer really to that question is what I said before that just over the last two or three years we just seem to have a real renaissance in how we’re working together and how excited we are about the music we’re making.

I think it will be the most boring thing in the world to make a Brexit album but, at the same time, we have been really impacted by what’s happening in the country in lots of different things – inequality and injustice, and I think we’re pleased we can get into electronic music and, you know, a depth of feeling that something is being expressed. We’re not gonna tell people what they’re gonna feel listening to that music, or how they’re gonna respond to it and we know that there’s something within us being expressed and I think that’s the important thing, you know… beyond what age we are or who we are.

Read Johnno’s 1993 interview with The Dust Brothers (as they were then known):

The Chemical Brothers’ ‘No Geography’ comes out on April 12th 2019 via Virgin EMI – buy the album here.